In the decade between its disastrous theatrical failure in 1982 and the more triumphant reception of its 1992 Director’s Cut, Ridley Scott’s science-fiction masterwork Blade Runner endured as a cult item with a small but loyal fandom. The film’s fortunes started to turn around with the accidental discovery of an unfinished workprint version screened as part of a 70mm film festival in 1990. Featuring a few small but dramatic differences in the movie, the Workprint Cut led to a re-evaluation of the picture and quickly paved the way for both the Director’s Cut and, eventually, the 2007 Final Cut.

Ironically, this same workprint had previously played for test audiences in early 1982 and was received so negatively at that time it caused the studio to panic and demand last-minute changes, including the addition of Harrison Ford’s divisive voiceover narration. Yet eight years later, seeing the movie again without that voiceover was likely the single biggest factor in the film’s redemption.

| Title: | Blade Runner: Workprint Cut |

| Year of Release: | 1982 |

| Director: | Ridley Scott |

| Watched On: | Blu-ray |

| Also Available On: | DVD |

At present count, four official versions of Blade Runner have received wide theatrical release. They break down as follows:

- 1982 American Theatrical Cut

- Voiceover (yes)

- Extra violent bits (no)

- Unicorn dream (no)

- Happy ending (yes)

- 1982 European Theatrical Cut

- Voiceover (yes)

- Extra violent bits (yes)

- Unicorn dream (no)

- Happy ending (yes)

- 1992 Director’s Cut

- Voiceover (no)

- Extra violent bits (no)

- Unicorn dream (yes)

- Happy ending (no)

- 2007 Final Cut

- Voiceover (no)

- Extra violent bits (yes)

- Unicorn dream (yes)

- Happy ending (no)

- Plus small additional changes

Rediscovered in 1990, the Workprint Cut serves as sort of an unpolished hybrid between these other versions. It opens with a different title credit and prologue text, and is missing the iconic close-up of an eyeball. It also has no end credits at all, just a “The End” card followed by music playing over an extended black screen.

The print has almost no voiceover narration from Harrison Ford, aside from one short passage during Roy Batty’s death scene different from the version used in the 1982 theatrical cuts. While the workprint does still have the violent cutaway shots found in the European theatrical cut (but trimmed from the American cut), it uses the slightly tamer version of Batty’s line, “I want more life, father,” rather than, “I want more life, fucker.”

The workprint does not include Deckard’s daydream about a unicorn, which Ridley Scott would later deem essential to the fabric of the movie. Nor does it include the tacked-on happy ending comprised of last-minute reshoots with Harrison Ford and Sean Young (and, according to legend, some outtake footage from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining). That part, Scott was pleased to discard from future versions.

Eagle-eyed fans may also glimpse a brief shot here or there unseen in either the 1982 theatrical cuts or the 1992 Director’s Cut. Some, such as a pair of go-go dancers in hockey masks working in the middle of a crowded city street, would wind up reinstated for the 2007 Final Cut. Others, including a different camera angle on Batty’s death, remain exclusive to the workprint.

Another significant difference in the workprint is that several long stretches of the movie play with temp music because the Vangelis score hadn’t yet been completed. In some cases, that can have a big impact on the tone of the scenes. This is especially notable during the film’s climax.

The screening of this workprint in 1990 caused a major stir among fans, who were blown away by how much better the movie played without the voiceover or happy ending. Judging by some interview footage on the later home video release, Ridley Scott himself wasn’t so thrilled about it. To be fair, that may be because he considered the workprint an unfinished product never intended to be seen again following its early test screenings. Nevertheless, the film’s producers were so encouraged by this reception that they were able to convince Warner Bros. to shell out some money for an official Director’s Cut restoration.

In order to time a splashy theatrical re-release around the movie’s tenth anniversary in 1992, Ridley Scott was forced to rush through a re-edit of the film, using the 1982 American theatrical cut as a base. He was able to pull out the Harrison Ford voiceover, chop off the happy ending, and insert his precious unicorn dream, but was not able to restore the extra bits of violence from the European theatrical cut, or perform any other fine-tuning or revisions at that time. Those would not happen until the eventual Final Cut in 2007.

In light of the subsequent versions to follow it, the Workprint Cut exists mostly as a curiosity and a footnote in the history of Blade Runner. It doesn’t contain very much exclusive footage that wouldn’t eventually make its way into the Final Cut, and it’s missing a couple of important pieces (such as the eyeball close-up and the unicorn dream) that fans may consider crucial. On that note, I wouldn’t recommend it as any new viewer’s first-time experience watching the movie, and it isn’t necessarily essential viewing for casual fans only interested in watching one definitive version.

However, for a work-in-progress creation, this workprint makes a remarkably coherent and nearly satisfying film even on its own. Any existing fan already schooled in the other versions of the movie would be well-served to spend a couple hours studying this one as well. Honestly, is there ever a bad excuse to watch Blade Runner again?

The Blu-ray

Blade Runner has been a perennially popular title on home video, issued and reissued multiple times on almost every format. The Director’s Cut was among the very first DVD launch titles in 1997. In December of 2007, Warner Bros. went all-out with 5-Disc Complete Collector’s Edition releases on both the Blu-ray and competing HD DVD high-definition disc formats – as well as even more deluxe Ultimate Edition box sets on both formats packaged to look like the metal briefcase a Blade Runner would carry to house a Voight-Kampff testing machine.

At that time, I wound up with a copy of the briefcase set on HD DVD. I still own it, though I haven’t tried to play any of the discs from it recently. Unfortunately, Warner HD DVD discs have proven to suffer a very high playback failure rate over time. Worried about this, I later decided to add the 30th Anniversary Collector’s Edition Blu-ray Digibook release to my collection in 2012, as well as the Final Cut on 4K Ultra HD when that came along in 2017.

Among the contents of both the original 5-disc set and the 3-disc Digibook are all four official theatrical versions of the movie. The 1982 Workprint Cut is also found as a bonus feature on a supplement disc in both packages.

The Workprint Cut is authored in 1080p high-definition. Sourced from a 70mm blow-up print, the image has been mildly cropped from its original 2.40:1 to 2.20:1. The picture is a little soft but generally has a decent amount of detail. The print is pretty grainy and worn in places, some worse than others. Colors and black levels are also somewhat dull. Gate-weave instability is very noticeable whenever text is on screen, and most of the last half of the movie suffers from light horizontal streaks across the top and bottom of the image.

All that said, the studio technicians were able to restore this workprint to a very watchable condition overall. Moreover, this print features the movie’s original color timing, without any of the obnoxious coating of teal that Ridley Scott smothered over the film for the 2007 Final Cut.

The Workprint Cut’s audio is provided in a lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track that may not be quite as goosed as either the Director’s Cut or the Final Cut, but still comes across pretty strong and has some decent bass action.

The Blu-rays came loaded with extras, especially the 5-disc set. Given that the workprint itself is effectively a supplement to the Final Cut, it’s hard to say which features belong to it rather than to Blade Runner in a general sense – other than the one-minute intro by Ridley Scott or the audio commentary by Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner author Paul M. Sammon, of course.

Authored onto the same disc as the Workprint in the Digibook are a half-hour featurette called All Our Variant Futures: From Workprint to Final Cut (which, despite the title, is almost entirely a promo for the Final Cut with very little talk of the other versions) and the exhaustively thorough 3.5-hour documentary Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner. A section with the deceptively simple title of “Access” stores a wealth of further featurettes, interviews, deleted scenes, screen tests, trailers, and other material that could take days to dig through. Disappointingly, most of it is encoded in standard-definition video.

Debating the Versions

While I believe the mainstream consensus would hold that Blade Runner was greatly improved by the changes made between the 1982 theatrical cuts and the 1992 Director’s Cut (the big ones being prompted by this Workprint Cut), at least some factions of the film’s fandom continue to prefer the movie with the Harrison Ford voiceover narration. The argument in its favor usually suggests that the voiceover gives the movie the flavor of an old-fashioned film noir.

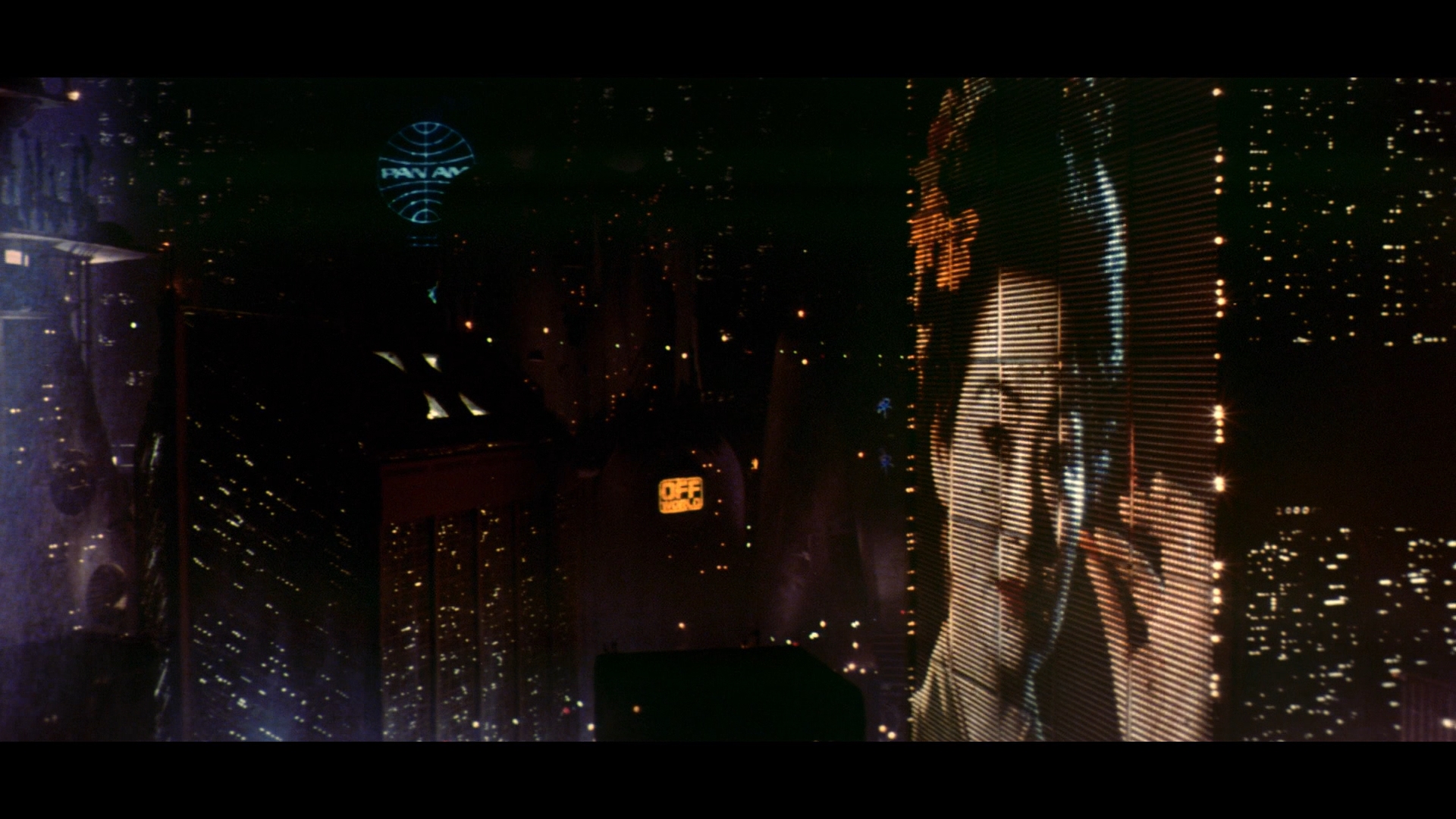

I can see some merit in that point of view, but personally, I side with the camp that Ford’s delivery is too flat and monotone (allegedly on purpose, as he recorded the voiceover under duress). The intrusion of narration also destroys any sense of awe during during Deckard’s first spinner flight over the city. One of the most important visual highlights of the entire film, that scene is much more majestic when the Vangelis score is allowed to swell without Ford talking over it.

I’ve also never been able to stand the cheap, tacked-on happy ending: “Remember that four-year lifespan thing the whole story revolved around? Well, good news, that doesn’t apply to Rachel! Hooray! We get to live happily ever after in this lush and thriving forest that’s been right outside our dystopian urban nightmare the whole time!” Nope. No thank you on that. The movie is immeasurably better without that stupid nonsense.

On the other hand, I find Ridley Scott’s beloved unicorn dream a little cheesy, and its implication that Deckard himself may be a Replicant undercuts Deckard’s character arc. As I see it, one of the main points of the story is that, as a human, Deckard has to learn how to see Replicants not just as things, but as people just as worthy of life as himself. But if Deckard’s been a Replicant the whole time too, that gets thrown out the window for a cheap plot twist.

So, taking all of that into account, with no voiceover, no happy ending, no unicorn dream, and no ugly teal tint, this Workprint Cut might almost be my favorite version of Blade Runner – if only the opening visual effects composite of that eyeball and the Vangelis score had been completed. Without those, however, I’m inclined to go with the 1992 Director’s Cut, which fixes my two biggest complaints (the happy ending and the voiceover) but hadn’t yet been turned into the goddamn teal atrocity we’d see with the Final Cut.

Related

- Ridley Scott (director)

- Harrison Ford

- Sean Young

- Sean Young & Daryl Hannah

I love the ‘I want more life, father’ instead of ‘fucker’. A much more urgent, emotional quote.

LikeLike

“Father” is also more relevant to the themes of the story. “Fucker” is just rude for the sake of being crass.

LikeLike

I think I like the Final Cut the best. Didn’t they fix a shot of the dove flying up into the sky during Batty’s death scene that didn’t look right in the DC from ‘92? And they did something else during one of Zhora’s scenes didnt they? I just remember a few minor things they were able to fix with CGI in 2007 that they weren’t in ‘92. To me it’s the most complete version of the movie. Ive heard people push back on the unicorn dream saying its actually Deckard thinking of one of Rachael’s implanted memories. So when Gaff leaves him the unicorn at the end its like a warning that they’re coming for her.

LikeLike

Yes, I do like some of the fixes in the Final Cut. The shot of the dove flying away from Batty now looks like a more appropriate skyline. Joanna Cassidy’s face has been composited over the obvious stunt double during Zhora’s death scene, and the lip sync was fixed to match the dialogue when Deckard confronts Taffy Lewis in the snake market (using facial capture from Harrison Ford’s son). I’m down with all those things. However, I just can’t stand the hideous new teal color grade, which is extremely heavy-handed and persistent through the entire movie.

LikeLike

I only discovered the movie around 2007 and The Final Cut was the first version I watched. As such, the color timing didn’t bother me since I gad nothing to compare it to. For all I knew, the movie was meant to look that way all along lol. There are some cases where the teal overload definitely bothers me. The 4k of Batman Returns for example is unwatchable imo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I honestly am starting to feel like this is my favorite cut of the film and all it’s really missing is that first eyeball shot and Vangelis’s score… but I only missed the latter in the final scenes with Roy Batty since the orchestral stuff just sounds cheesy at the end of the film. I’m less convinced that the choice to overlay more Vangelis tracks onto other scenes was the right way to go.

I actually preferred the other more minimal, unnerving synths and chimes during the “love” scene and the “JF Sebastian visit/convincing” scene, both of which became appropriately more menacing (and effective, imo) without the airy or saxophone-inflected Vangelis tracks.

LikeLiked by 1 person