In my article series The Philosophy of 2.35:1 Constant Image Height, I attempted to explain what Constant Image Height (CIH) display is, how it differs from watching content on a traditional 16:9 television or home theater screen, and why it’s important. For this first addendum, we’ll examine the mechanics of setting up a CIH system and troubleshoot some common obstacles that may arise.

PREVIOUS ARTICLES:

- PART 1: WHAT IS CONSTANT HEIGHT DISPLAY?

- PART 2: “WIDESCREEN” NOT “SHORTSCREEN”

- PART 3: THE IMAX PROBLEM

IN THIS ARTICLE:

- 2.35:1 vs. 2.39:1 vs. 2.40:1

- THE ZOOM METHOD

- ANAMORPHIC LENSES

- OTHER ASPECT RATIOS

- IMAX AND VARIABLE ASPECT RATIO CONTENT

- CIH+IMAX

- CONSTANT IMAGE AREA

- UNREADABLE SUBTITLES

2.35:1 vs. 2.39:1 vs. 2.40:1

Even though this site extensively uses the terms “2.35:1” and “scope” in reference to Constance Image Height, you should be aware that these phrases are typically shorthand and may not be technically accurate in many cases.

As it debuted in 1953 with The Robe, the original CinemaScope format developed by 20th Century Fox had a wide aspect ratio that measured 2.55:1 on screen. Fox reduced the specs to 2.35:1 a few years later in order to accommodate stereo audio on the film prints. However, Fox’s CinemaScope itself was defunct by the end of 1967 and was supplanted by competitor Panavision, which offered very similar but optically superior anamorphic lenses.

Panavision emulated the CinemaScope 2.35:1 ratio at first, but amended it to 2.39:1 in 1970 in order to fix an issue with flashing at the top of the frame. The theatrical standard for anamorphic widescreen projection has been 2.39:1 ever since. This has carried through even to later photographic formats (including digital) that may not use anamorphic lenses for image capture anymore. Yet, somehow, the terms “2.35:1” and “scope” have stuck around, even among many industry professionals, despite not being technically or mathematically correct.

That being the case, shouldn’t a Constant Image Height home theater screen measure 2.39:1? Maybe. But also, maybe not.

The problem is that, regardless of theatrical projection standards, there is no guarantee that a 2.39:1 movie will be transferred at a precise 2.39:1 ratio on home video. Depending on how the video transfer equipment is calibrated, you may wind up with anything in a range from 2.30:1 to 2.40:1 – the most common results being 2.35:1 and 2.40:1. This applies to movies (and lately TV shows) made after 1970 right up to today as much as it does to those made when the standard was actually 2.35:1.

Take, for example, three sequential James Bond films: The World Is Not Enough (1999), Die Another Day (2002), and Casino Royale (2006). These movies were all made well after the standard changed to 2.39:1. Yet once you remove the letterboxing, the active movie image in the Blu-ray edition of The World Is Not Enough measures 1920×816 pixels (2.35:1) while Die Another Day measures 1920×804 (2.39:1) and Casino Royale measures 1920×800 (2.40:1).

.

.

There is frankly no technical reason for this to be the case, other than happenstance. On a 16:9 TV or monitor (on which all of these video masters were likely prepared), the difference between these ratios is small enough that most viewers will probably not notice it. Only on a Constant Image Height screen will this be an issue.

On a 2.35:1 screen, movies with wider ratios such as 2.39:1 or 2.40:1 will have small letterbox bars on the top and bottom. On a 2.40:1 screen, a 2.35:1 movie should have small pillarbox bars on the sides, if aligned for true Constant Height.

On top of all this, placing a 1.33x anamorphic lens in front of a 16:9 home theater projector (more on this below) will stretch the image output to 2.37:1., which hardly matches any movie’s true aspect ratio.

So, what type of screen should you install – 2.35:1, 2.37:1, 2.39:1, or 2.40:1? Some home theater users really stress over this.

In my opinion, this is a lot of consternation over what ultimately amounts to a trivial issue. No matter which aspect ratio screen you install, it will never fit all “scope” movies perfectly at all times, because there is no perfect standard for what aspect ratio a scope movie will be. My advice is to just pick whichever ratio you favor or is most convenient for you to purchase, and then deal with content that doesn’t fit as needed. Some users will choose to keep every pixel visible with black bars framing the image. Others will adjust their zoom settings to shave off tiny slivers of picture, either on the sides or on the top and bottom depending on the content, to fill the screen area. This is entirely a matter of personal preference. Either option falls within the expected tolerances for projection at professional movie theaters, where a small margin of error around the edges is extremely common.

Personally, I chose to install a 2.35:1 screen and am not bothered by the small letterbox bars on 2.40:1 content. I will also continue to use the phrase “2.35:1” in relation to Constant Image Height, acknowledging that it is meant to also encompass ratios up to 2.40:1. I believe that term is more commonly recognized and understood even by layman readers, and I would prefer not to confuse the issue by getting picky over math.

The Zoom Method

The most common implementation of Constant Image Height requires only a home theater projector and a scope screen. The projector must have enough optical zoom range to fill the top and bottom of the frame with a movie’s active image at either 16:9 or 2.35:1 aspect ratios. Preferably, a model with automated lens memory presets is most helpful to switch between ratios with just a button press or two.

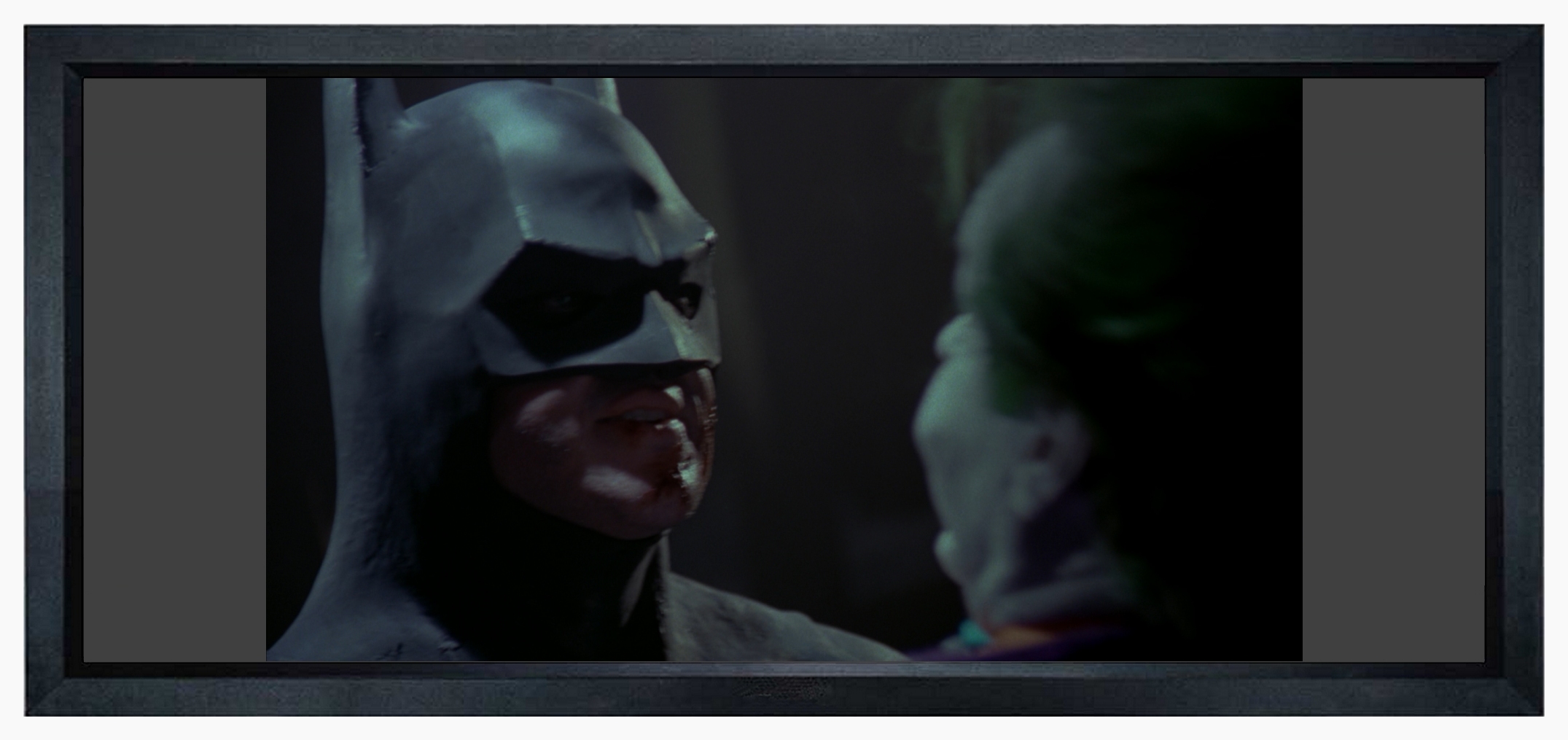

For films or TV shows with a narrower aspect ratio, you’ll use a reduced zoom to center a 16:9 image in the middle of the screen, leaving the sides unlit. Below is a shot from Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), which played theatrically at 1.85:1 but was transferred slightly open-matte to 16:9 for the initial DVD and Blu-ray releases.*

In actual practice, the unused portions of the screen should appear near black in a darkened room, but I’ve lightened them to gray for all of the following illustrations in this article in order to better distinguish them from video content.

For movies or shows that use a wider scope aspect ratio, like Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins (2005), zoom up until the 2.35:1 image completely fills the screen, allowing the empty black letterbox bars to spill over onto your wall. Once the lights in the room are turned off, you shouldn’t notice the letterbox bars anymore.

If you want to get fancy about it, motorized curtains or masking panels that draw in or sweep out as you change aspect ratio settings can add a fun sense of flair and showmanship, but in most cases they aren’t necessary to make Constant Image Height work.

*Note: A later 4K Ultra HD remaster of Batman restored the original 1.85:1 matting, but that master was also given a gaudy teal-and-orange color grade that I personally find very unappealing. Some of the original sound effects were also replaced with very different sounds for no clear reason. I default to watching the older Blu-ray, despite its own picture quality deficiencies.

Anamorphic Lenses

Advanced users may go to the trouble of mounting an expensive anamorphic lens, such as a Panamorph Paladin or Paladin DCR, in front of the projector. Panamorph is the brand I have the most personal experience using. Unfortunately, the optics on older Panamorph lenses such as the UH480 or the CineVista cannot pass 4K detail. However, the Paladin line is designed for 4K projection. I cannot speak for other competing lens manufacturers, such as ISCO or Prismasonic, as I have not tested their products myself.

Anamorphic lenses for home theater come in two varieties: either horizontal expansion or vertical compression. (Panamorph currently only offers vertical compression models for 4K.) These are two different methods to achieve the same goal. A horizontal expansion lens will stretch a 16:9 letterboxed image from side to side, while a vertical compression lens will squeeze that same image shorter from top to bottom. In either case, you wind up with a picture that looks geometrically distorted at first.

Obviously, you would not want to watch a movie this way. The lens is intended to be used in conjunction with electronic scaling and (if a vertical compression type) the projector’s optical zoom. The scaling should stretch the picture vertically and crop off the letterbox bars. Many home theater projectors offer aspect ratio scaling modes designed for this, but this step could also be performed in other devices, such as certain models of Blu-ray and Ultra HD disc players or external video processors.

Once the image geometry is restored, adjust the zoom size to make the movie fill your CIH screen, the same height as 16:9 content but now wider.

Using an anamorphic lens in this fashion allows you to utilize the projector’s entire pixel panel for the 2.35:1 movie picture itself, without letterboxing. While scaling will not add real picture detail that wasn’t present in the source, it will increase pixel density in the image and potentially reduce the visibility of pixel structure on large screens. To be honest, that’s not a terribly relevant concern with today’s 4K projectors, which have more than enough resolution even for the largest home theater screens. More to the point, the lens will redirect light previously wasted on letterbox bars into the movie image, increasing brightness. Lighting up a large screen can be a challenge for many projectors, especially as the lamp ages and dims. The extra brightness will also benefit HDR material, which needs all the light output it can get to emphasize peak highlights.

The primary downside to an anamorphic lens is cost. A good lens requires quality optics to ensure that all important picture detail gets passed with none rolled off. Sadly, that doesn’t come cheaply. The lens add-on may cost as much or more than your projector.

The other notable problem is that anamorphic lenses only work optimally to project scope images with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. To watch 16:9 content, you’ll either need to remove the lens from the light path with a sled mount (another expense) and turn off scaling, or use a different scaling mode to reduce the image width and pillarbox it into the center of the scope frame. The latter will effectively toss out some resolution – and potentially picture detail – from the image source. Generally speaking, that’s usually not noticeable, but some viewers will be more bothered by the idea of it than others.

Other Aspect Ratios

Theatrical feature films mostly come in three main aspect ratios – 1.37:1 for pre-1953 classics, then 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 afterward. However, specialty formats over the years have played with other image shapes. Movies shot on 65mm film stock (such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968) have a native aspect ratio of 2.20:1. Titles filmed in the VistaVision process (e.g. 1954’s White Christmas) were designed to be flexible for projection at 1.66:1, 1.85:1, or 2.00:1. As explained in my Part 3 article, IMAX film stock has a shape of 1.44:1, and some movies play in IMAX theaters with a Variable Aspect Ratio configuration. Other variances and oddities have also appeared through the decades.

Additionally, a great many television series these days are broadcast or streamed in aspect ratios that fall somewhere between 16:9 and scope. Most prevalent among these are 2.00:1 (popular examples include Netflix’s Stranger Things or Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale) and 2.20:1 (CW’s Superman & Lois, HBO Max’s Doom Patrol).

All of this content will require some adjustment to display on a 2.35:1 screen.

Anything narrower than 16:9 should be easy enough to handle. With HD or Ultra HD formats, ratios such as 1.33:1 (4:3), 1.37:1, or 1.66:1 are authored on home video inside a 16:9 container with black pillarbox bars on the sides. Simply treat these the same as you would 16:9 material, either via zoom or scaling. The electronic pillarboxing will fill in the missing screen width. (Again, in practice the black pillarbox bars should blend seamlessly with the unlit portions of the screen. The images I’ve created here exaggerate the shading difference for illustration only.)

If your screen is 2.35:1, you’ll have to accept a small amount of letterboxing on any content wider than the screen. Ben-Hur (1959) was filmed in the short-lived MGM Camera 65 process at 2.76:1.

More recently, director Quentin Tarantino revived this format (technically under the competing Ultra Panavision 70 branding) for his Western The Hateful Eight (2015).

Some dedicated enthusiasts may go to the trouble of installing extra wide screens so that the image height will truly remain constant even with such extreme examples. Realistically, movies like this are so rare that most viewers put up with the compromise of letterboxing on such a small handful of titles.

Ratios between 16:9 and 2.35:1 can be adapted to CIH without too much difficulty if using the Zoom Method. 1.85:1 theatrical features are so close to 16:9 that many users choose to simply watch them at the 16:9 preset, while others will zoom them slightly to maintain true Constant Height. For that, and for ratios such as 2.00:1 and 2.20:1, you should save several zoom presets in the projector with the appropriate amount of magnification to let the image fill the height of the screen while the letterbox bars fall off onto the wall.

Frustratingly, these in-between ratios are more difficult to manage with an anamorphic lens in place. The combination of stretching and scaling that works for 2.35:1 will crop too much image off the top and bottom of the picture. The best way to cope with this is to use a video processor with comprehensive aspect ratio control, such as a Lumagen Radiance Pro or MadVR Envy. Admittedly, the expense of those can be off-putting.

Failing that, the only solution is to start with the image stretched by the anamorphic lens.

Scale that down to the 16:9 preset , leaving you with bars on all sides.

Finally, optically zoom back up until the image fills the height of the screen.

This may be regarded as less than ideal, since it combines both the pixel resolution loss of the scaling with the light loss from the zooming, but the degree to which this is noticeable or objectionable will be up to each user to decide.

IMAX and Variable Aspect Ratio Content

By far the biggest obstacle to implementation of Constant Image Height projection is the matter of movies and television shows that employ a Variable Aspect Ratio (VAR) that changes the shape of the image scene-to-scene or even shot-to-shot. While a movie like Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008) will properly fill a 2.35:1 screen in many scenes, select sequences shot on IMAX film expand in height and will overshoot the top and bottom of the screen when projected using the Zoom Method.

I wrote about the conflict between IMAX and CIH at length in Part 3. Now we’ll focus on ways to watch such content on a 2.35:1 screen.

- Method 1: Reduce the projector’s zoom.

The quickest and easiest alternative, albeit certainly not the most appealing, is to reduce the projector’s zoom setting to the preset normally used for 16:9 content. This will allow any 16:9-formatted scenes to fill the height of the frame in pillarboxed format with nothing the wall.

Of course, this will also result in all of the 2.35:1 footage (often a larger percentage of the movie’s running time) being shrunken down to a small rectangle windowboxed in the center of the screen with black bars on all sides, which defeats the point of having a 2.35:1 screen in the first place.

- Method 2: Crop the IMAX footage to scope 2.35:1.

Some viewers will object to the idea of cropping a movie picture to make it fit their screen, citing concerns of artistic intent and the old horrors of the pan & scan days. However, IMAX VAR movies ought to be considered a carve-out exception to the rule of “OAR” (Original Aspect Ratio). Films like these are composed for multiple aspect ratios during production, with the intention of being projected at Constant Height 2.35:1 in all other (non-IMAX) cinemas. Cropping the home video copy is an attempt to mimic that theatrical presentation.

Projector owners have two main ways to accomplish this in the home. Those who have installed an anamorphic lens in front of the projector should simply choose the preset they would use for any other 2.35:1 movie. The same combination of optical stretching with the lens and digital scaling in the projector (or other external device) that cuts off the black bars from letterboxed movies will also remove the equivalent top and bottom portions of a 16:9 image.

If that isn’t possible, many home theater projectors offer a “blanking” feature that will black out specific rows of pixels, essentially turning parts of the picture into letterbox bars. After that, you should be ready to zoom.

Either process can be applied to the 16:9 or 1.90:1 scenes in a VAR movie.

Doing so will give the film a consistent 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

Many (perhaps even most?) of these IMAX VAR movies are photographed such that the intended 2.35:1 extraction is taken directly from the center of the image. In such a case, proportionally cropping or blanking the 16:9 frame should give you a nearly exact match to the 2.35:1 theatrical version.

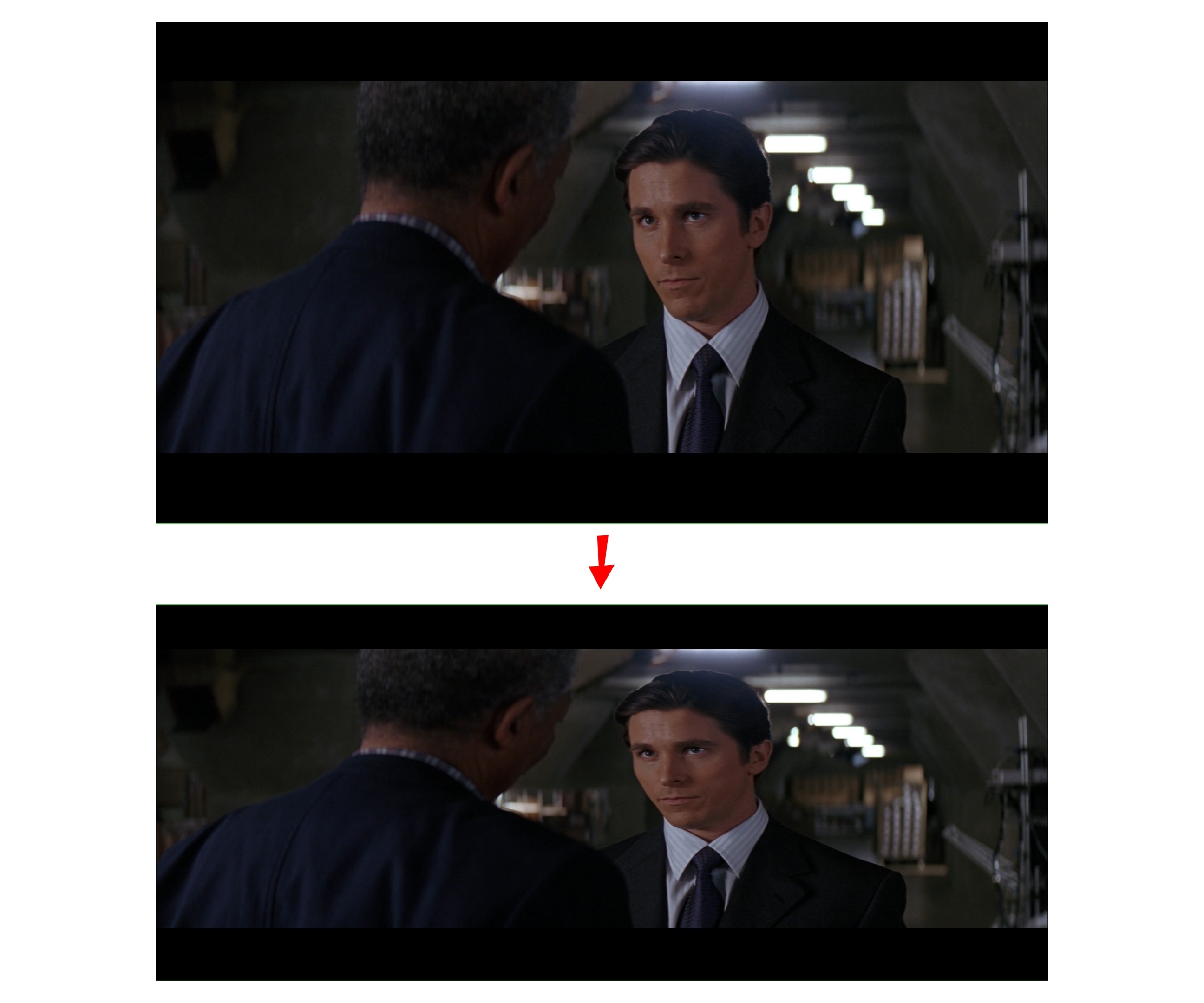

Regrettably, that isn’t always guaranteed to work. Some filmmakers will manually adjust the photographic framing during post-production. In fact, director Nolan did exactly that for The Dark Knight, moving the 2.35:1 extraction higher or lower in the frame on a shot-by-shot basis to derive what he considered the best 2.35:1 version of the movie. If you compare the 2.35:1 cropping example I just made above to the director’s own prepared 2.35:1 edition (available on DVD and streaming), you can see that Nolan moved the frame in this shot up a bit to give the character more headroom.

In many other shots, the frame is moved lower, to take the 2.35:1 extraction from the bottom half of the IMAX negative.

For The Dark Knight specifically, I personally feel that the majority of these differences are not noticeable without a direct comparison, and most CIH viewers could watch the Blu-ray or Ultra HD editions cropped to 2.35:1 without finding anything amiss.

I wish I could say that were true for every movie, but things don’t always work out that way. For example, in the VAR version of Star Trek into Darkness (available in the Star Trek: The Compendium Blu-ray box set, the Ultra HD Blu-ray, and the “IMAX Enhanced” streaming edition), critical on-screen text and graphics have been re-positioned in the frame to edge outside the 2.35:1 safe zone.

CIH viewers are advised to instead watch the normal 2.35:1 Blu-ray and streaming editions, for which the same text and graphics remain inside the scope frame area.

If no CIH 2.35:1 version exists, sometimes partially reducing zoom and cropping to a slightly narrower ratio such as 2.20:1 or 2.00:1 will yield an acceptably framed image without compromising image size quite as badly as a full 16:9 windowbox.

Additionally, some recent movies and TV series have used Variable Aspect Ratio formatting in ways that have nothing to do with IMAX and may not be safe to crop to 2.35:1. Director Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) and The French Dispatch (2021) playfully jump around scene-to-scene from 4:3 to 1.85:1 to 2.35:1 and other ratios. All of this is framed within a 1.85:1 container, and the black letterbox or pillarbox bars are an intentional part of the design aesthetic. Watching in Constant Height is neither possible nor necessarily even desirable.

An even more challenging example is the Netflix superhero drama Jupiter’s Legacy (2021), which presents scenes set in the modern day in scope 2.35:1 while flashback scenes to the 1920s are full-screen 16:9.

Because the 16:9 scenes feature a lot of medium shots and close-ups composed without much headroom, cropping them to 2.35:1 cuts out important picture information and looks very poor.

CIH viewers are therefore left with little choice but to reduce the projector zoom all the way to the 16:9 preset and watch the 2.35:1 portions in shrunken windowbox format. Later seasons of Amazon’s sci-fi drama series The Expanse (2015-2022) have similar issues.

- Method 3: Buy a very expensive video processor.

Technological innovation can overcome some of these obstacles, but at a steep price. The MadVR Envy home theater video processor offers a feature called “Black Bar Detection” that will analyze the content being watched and determine the aspect ratio of each frame. It can then – in real time – scale the image up or down to maintain Constant Image Height formatting, with the wider aspect ratios filling the screen width and narrower ratios pillarboxed in the center. Of course, to get this, the Envy has a daunting MSRP as expensive as or more expensive than a good home theater projector.

To be fair, this boutique product also offers a host of other advanced functions that may justify the cost to consumers who need them. While a free version of MadVR processing is also available for Home Theater PC users, that program requires a high-end graphics card and PC specs that won’t come cheaply either. HTPCs are complicated and often impractical, and may be limited in the types of content sources you can play on or through them. I don’t generally recommend them except to advanced users with the skills to build and configure them.

Black Bar Detection would very efficiently resolve the problem with shows like Jupiter’s Legacy or The Expanse that could actually benefit from Constant Image Height formatting if they were presented that way. IMAX VAR movies like The Dark Knight or Star Trek into Darkness, on the other hand, still leave one nagging doubt. Scaling the 16:9 or 1.90:1 IMAX footage down to pillarbox format in the center of a CIH frame violates the original intent that those scenes be larger and more immersive than the 2.35:1 footage around them. In truth, it does precisely the opposite by making them smaller and diminished in scale. By one line of thinking, cropping the IMAX scenes to 2.35:1 CIH may be closer to the artist’s intent if the work is to be projected onto a 2.35:1 screen.

Note: The comparably-priced Lumagen Radiance Pro includes a similar Black Bar Detection feature, but reportedly that unit cannot change aspect ratios on the fly quickly enough to be of use during real-time movie watching. I’ve even heard a complaint that MadVR may not always be fast enough, but have not had the opportunity to test it myself.

CIH+IMAX

Any of the above methods involve some degree of compromise to make an IMAX VAR movie watchable on a 2.35:1 screen. Admittedly, content like this is perhaps best served on a 16:9 ratio screen, where the IMAX footage can be watched without cropping or shrinking. That said, it hardly seems right to watch an IMAX movie the same size as any average TV soap opera or game show, while scope 2.35:1 movies are relegated to the smallest available image size. Because so few true IMAX movies actually exist, a standard 16:9 screen will invariably prioritize and elevate content that was not photographed or composed for IMAX levels of immersion.

Another possible solution, and arguably the only one that maintains the artistic intentions of each photographic format, is a process that has been dubbed “CIH+IMAX.” The idea behind this technique is to install an oversized 16:9 screen with dark masking panels semi-permanently applied to the top and bottom portions, leaving a 2.35:1 viewing area in the center.

Under normal viewing conditions, this screen would be used as if it were a 2.35:1 CIH aspect ratio. Typical 16:9 TV or movie content, such as the below image from Star Trek: Enterprise (2001-2005), will appear inset within the 2.35:1 framing area. (Keep in mind that the screen should be sized appropriately so that such 16:9 material will be as large as you enjoy watching it, and the black masking will obscure the screen frame edges in the dark. If you feel that the 16:9 image is too small, that isn’t a flaw in the concept of Constant Image Height; your screen just isn’t large enough.)

A scope 2.35:1 movie will then expand horizontally, maintaining the same image height but greater width, as designed.

For the rare instances where a movie includes genuine IMAX footage, the masking panels should be removed, allowing the IMAX scenes to fill the entire screen area, both wider and taller than run-of-the-mill 16:9 despite technically being the same aspect ratio.

In some ways, this is the ideal approach to resolve the conflict between Constant Image Height and IMAX Variable Aspect Ratio. Scope content is wider than 16:9, and IMAX is larger than both.

If this method has any downsides, an extra large 16:9 screen may not always be practical or possible to install in a home theater, especially not when the full screen size would be used so rarely. Even assuming your room has enough wall space to accommodate one, a larger screen will be more expensive. Masking panels add further cost, and the need to manually add and remove them can become a burden. If anything, user apathy is likely to result in the panels being left off most of the time, which in turn will encourage the viewer to magnify typical 16:9 content to fill the screen, thus once again normalizing everyday TV shows and commercials as the largest thing watched, undermining any pretense of Constant Image Height.

Ultimately, home theater owners will need to decide for themselves how they prefer to deal with IMAX movies like these when they turn up. Thankfully, they are still a relative rarity.

Constant Image Area

Not every projector owner will be able or willing to fully embrace the practice of Constant Image Height. Some may have room constraints limiting the amount of wall space available. Others, while acknowledging that a 16:9 screen short-changes scope movies, may still wish to prioritize certain 16:9 content (such as sports or video games) and favor projecting them taller than a CIH screen. A popular compromise in these situations is an approach called Constant Image Area (CIA), which generally entails installing a screen of about 2.00:1 aspect ratio.

Although neither 16:9 nor 2.35:1 material will fit such a screen perfectly, both will be displayed with approximately the same amount of black bars on either the sides or the top and bottom, hence the description of using the same amount of overall screen area.

Although this may not always fully equalize the scale of objects in both types of movie (as described in Part 2), it comes much closer than a 16:9 screen and is generally a more tolerable compromise so long as you aren’t put off by the (smaller here) letterboxing or pillarboxing.

Another benefit to this type of screen is that it will precisely fit any content with a 2.00:1 aspect ratio, including many hundreds of TV shows and television movies available on streaming platforms.

Unreadable Subtitles

Constant Image Height projection users are a small niche within the home theater community, and an even tinier sliver of the greater home video market. The people who actually author home video editions of movies rarely give us much thought, and typically assume that all of their customers own only standard 16:9 televisions. As a result, they sometimes make seemingly innocuous choices that most viewers will give little thought, but which can have very negative repercussions for those watching on CIH screens. One of those issues is the question of where to place subtitles on a letterboxed image.

When you watch a foreign-language film in a commercial movie theater, any subtitle translation will appear within the movie image near the bottom of the screen. When that movie comes to home video, however, subtitles may wind up moved below the movie image, down into the lower letterbox bar. Here’s an example from the domestic Blu-ray edition of Zhang Yimou’s Mandarin-language House of Flying Daggers (2004).

This isn’t a problem on a 16:9 screen, but the lower line of text will get cut off on a 2.35:1 screen, effectively making the movie unwatchable for anyone who doesn’t speak Mandarin.

Fortunately, if you’re watching this movie on a physical media format like DVD or Blu-ray, some models of disc player offer the ability to manually adjust the subtitle position and move the text up into the frame. I have an OPPO Ultra HD Blu-ray player that I use for this. OPPO left the home video market a few years ago and no longer makes disc players, but the function is still available in some current Panasonic Blu-ray and Ultra HD players. Although it’s not typically a standard feature, other brands (or at least specific models within a brand) may include it as well.

Sadly, you’re probably out of luck if watching the movie via streaming. I’m not aware of any streaming media player that offers this subtitle movement feature.

In that case, or if you simply don’t happen to own one of the special disc players that can do it, the best available compromise is to partially reduce your zoom magnification (usually to approximately the same width area a 2.20:1 image would occupy) while shifting the picture upwards.

This is certainly not ideal, but so long as you keep the top of the movie flush with the top of the screen, and zoom out only enough until the subtitles come back into view, the movie image should still be larger and have smaller black bars than shrinking it all the way down to 16:9 size would be.

LikeLiked by 1 person